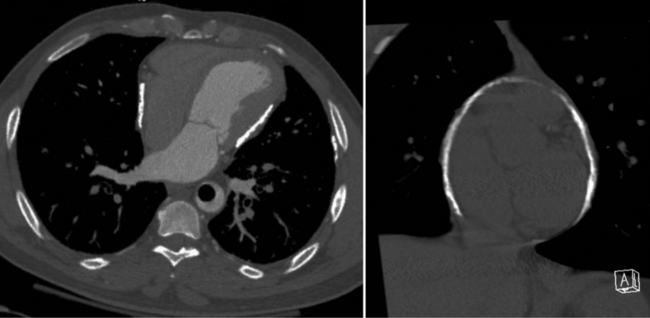

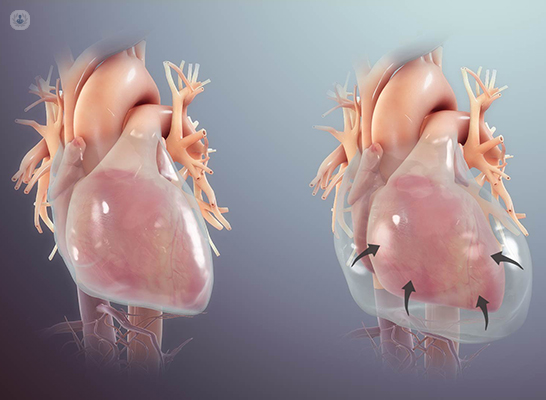

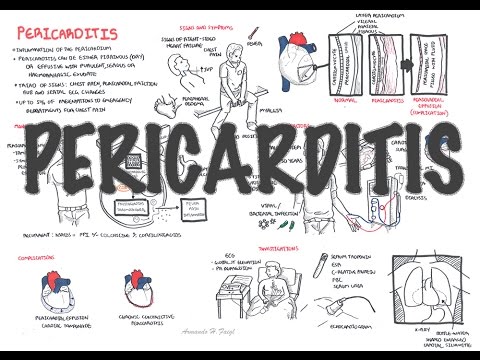

The two most serious complications of pericarditis are an effusion causing cardiac tamponade and constrictive pericarditis. Cardiac tamponade occurs when a pericardial effusion becomes large enough to impair contraction of the heart. Symptoms of cardiac tamponade include dyspnea, chest discomfort, fatigue, fluid accumulation in the body , and low blood pressure . In severe cases, cardiac tamponade can impair cardiac function to the point where it compromises delivery of blood and oxygen to the organs . Constrictive pericarditis is a consequence of chronic pericardial inflammation and is characterized by scarring and loss of elasticity of the pericardium. The main symptoms of constrictive pericarditis are dyspnea, edema, shortness of breath when lying flat and chest pain.

Overall, most patients can live a productive life with a very low risk of mortality related to recurrent pericarditis. Myocarditis and pericarditis are inflammatory conditions of the heart commonly caused by viral and autoimmune etiologies, although many cases are idiopathic. Emergency clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for these conditions, given the rarity and often nonspecific presentation in the pediatric population.

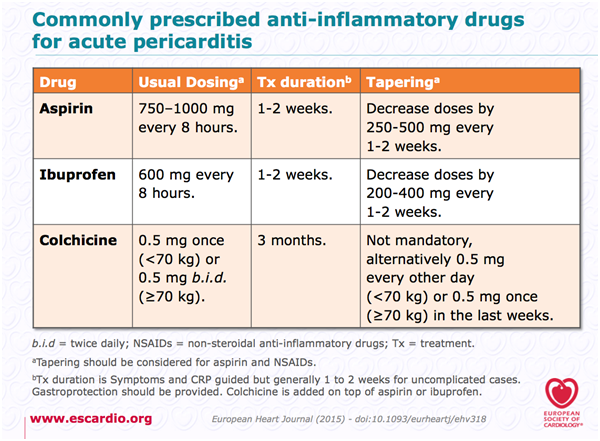

Children with myocarditis may present with a variety of symptoms, ranging from mild flu-like symptoms to overt heart failure and shock, whereas children with pericarditis typically present with chest pain and fever. The cornerstone of therapy for myocarditis includes aggressive supportive management of heart failure, as well as administration of inotropes and antidysrhythmic medications, as indicated. Children often require admission to an intensive care setting. The acute management of pericarditis includes recognition of tamponade and, if identified, the performance of pericardiocentesis. Medical therapies may include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine, with steroids reserved for specific populations.

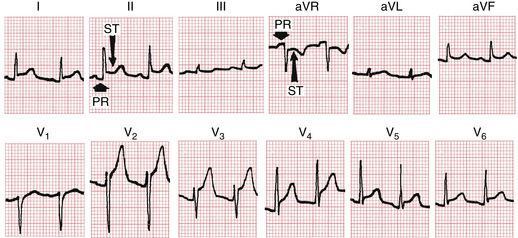

This review focuses on the evaluation and treatment of children with myocarditis and/or pericarditis, with an emphasis on currently available medical evidence. After gathering a complete history and performing an appropriate physical examination, certain tests will be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis. An electrocardiogram, which measures electrical activity of the heart, might show characteristic changes associated with pericarditis and can help rule out other cardiac causes of chest pain. Blood levels of troponin, a protein that is released into the blood following damage to cardiac muscle, are also useful to differentiate pericarditis from other heart conditions.

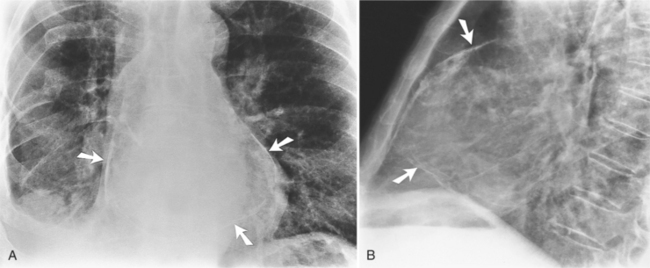

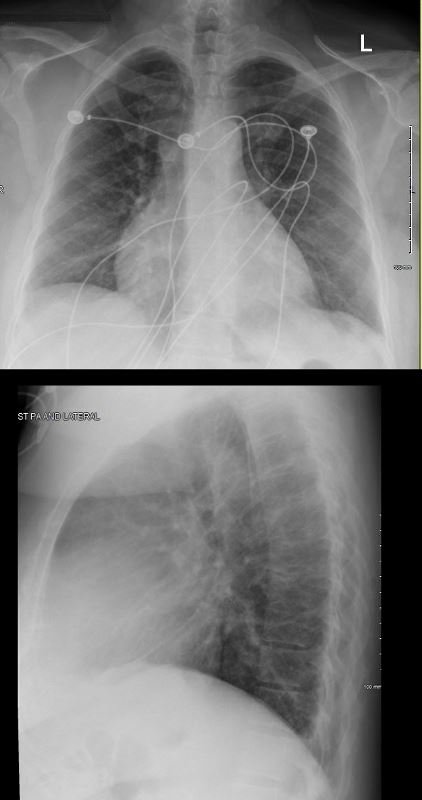

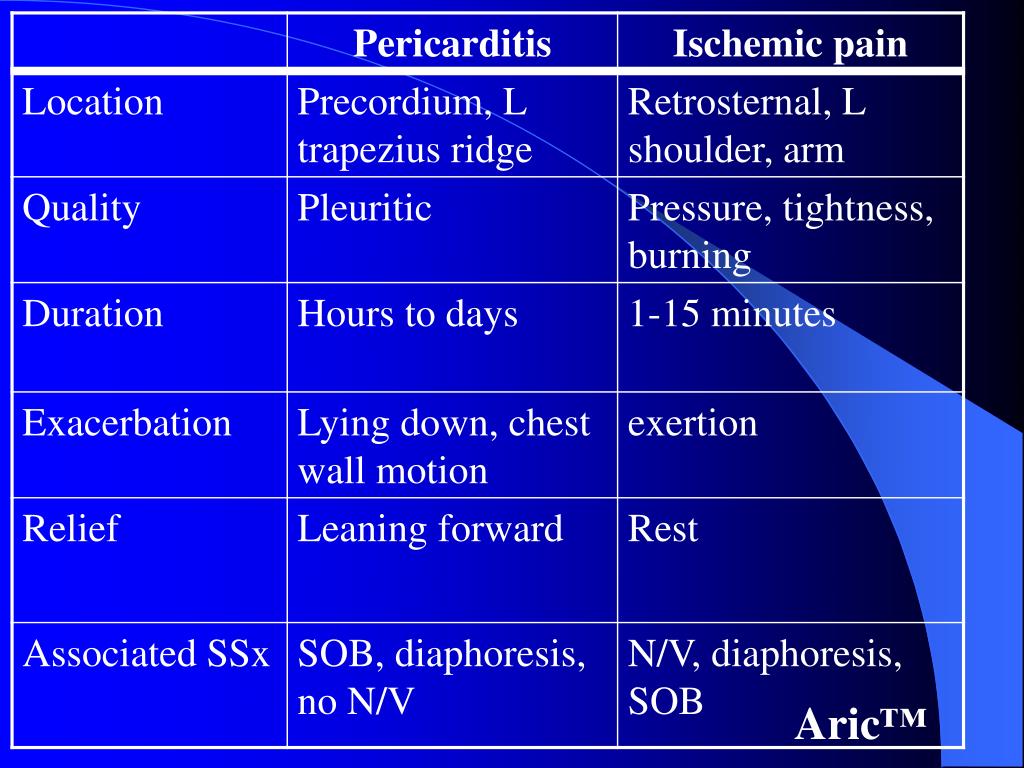

Troponin levels are usually normal in isolated pericarditis but are elevated in myopericarditis, myocarditis and myocardial infarction. Routine imaging tests include a chest X-ray, which is usually normal in pericarditis but can show signs of an alternative diagnosis or a pericardial effusion if it is large. An echocardiogram, an imaging method that uses sound waves to evaluate the anatomy and function of the heart and pericardium, is also routinely performed in patients with suspected pericarditis. The main symptom of pericarditis is chest pain, which is present in the vast majority of affected individuals. Typically, the pain is described as sharp and worse when coughing or taking a deep breath . The typical pain seen in pericarditis is also worse when lying down and is partially relieved when leaning forward.

Other symptoms that are associated with pericarditis include shortness of breath , fever, fatigue, malaise and the sensation of an irregular heartbeat . Another feature frequently seen in pericarditis is accumulation of fluid in the space between the heart and the pericardium , which is known as a pericardial effusion. The symptoms seen with a second or subsequent episode of recurrent pericarditis are often similar to the first event, although they tend to be less severe with recurrences. Although the symptoms of pericarditis can significantly affect quality of life, affected individuals typically have no symptoms between episodes. The number of episodes of recurrent pericarditis varies greatly between patients. Symptoms typically include sudden onset of sharp chest pain, which may also be felt in the shoulders, neck, or back.

The pain is typically less severe when sitting up and more severe when lying down or breathing deeply. Other symptoms of pericarditis can include fever, weakness, palpitations, and shortness of breath. The onset of symptoms can occasionally be gradual rather than sudden.

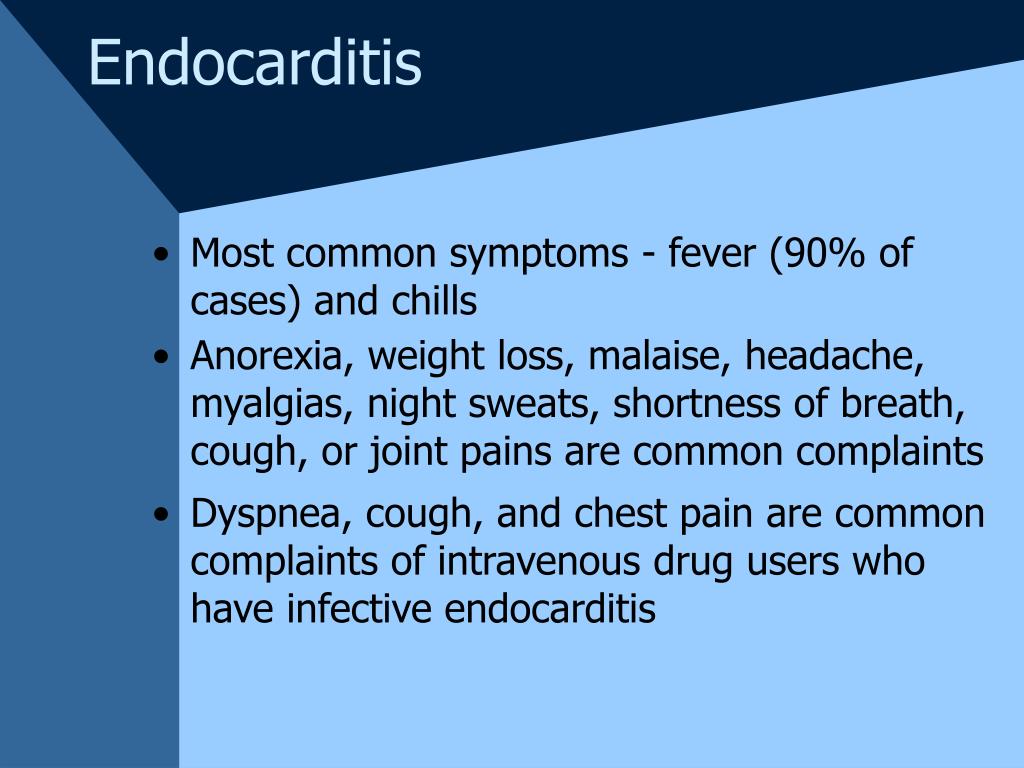

Myocarditis is an inflammation of the heart muscle, while pericarditis is an inflammation of the lining around the heart. Both conditions can result from an infection (including COVID-19), exposure to a toxic substance or radiation, or other health events. Symptoms can include chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations (feelings of having a fast-beating, fluttering or pounding heart).

In many cases, these conditions are mild and require little to no treatment. Rest is usually recommended in acute pericarditis and acute myocarditis. Given that myocarditis often leads to hospitalization, this task seems easy to carry out in hospital practice; however, it could be a real challenge at home in daily life.

Heart rate-lowering treatments (mainly beta-blockers) are usually recommended in case of acute myocarditis, especially in case of heart failure or arrhythmias, but level of proof remains weak. Calcium channel inhibitors and digoxin are sometimes proposed, albeit in limited situations. Whether heart rate has an effect on inflammation remains unclear. Several questions remain unsolved, such as the duration of such treatments, especially in light of new heart rate-lowering treatments, such as ivabradine. In this review, we discuss rest and heart-rate lowering medications for the treatment of pericarditis and myocarditis.

We also highlight some work in experimental models that indicates the beneficial effects of such treatments for these conditions. Finally, we suggest certain experimental avenues, through the use of animal models and clinical studies, which could lead to improved management of these patients. Be alert to the signs and symptoms of myocarditis and pericarditis when individuals present with chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations or other signs and symptoms following immunization with a COVID-19 vaccine.

Cardiology consultation for management and follow-up should be considered. Acute pericarditis causes chest pain, which may be very difficult to discern from pain caused by acute myocardial infarction. The chest pain in acute pericarditis may be severe and the patient may also experience cold sweats, tachycardia and anxiety; all of which are common in acute myocardial infarction. Clinical examination may reveal pericardial friction rub and the echocardiogram may show increased fluid in the pericardial cavity . Hemodynamic compromise may occur if accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac compromises the relaxation and/or contraction of the ventricles and atria.

This situation is referred to as cardiac tamponade, which has been discussed earlier. Recurrent pericarditis is a disease characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation of the pericardium, which is the sac containing the heart. The main symptom associated with an episode of pericarditis is chest pain that is typically sharp and worse when taking a deep breath . The first-line therapy for pericarditis, including for recurrent cases, is a combination of colchicine and either aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen. Although recurrent pericarditis can significantly affect quality of life, it is typically not life threatening or associated with serious illness, and patients are usually well between episodes. In contrast, chest pain, irregular heartbeat, heart palpitations, shortness of breath and light-headedness could indicate myocarditis or pericarditis.

Symptoms of these conditions have generally occurred within seven days of vaccination. Anyone who experiences these symptoms should seek medical attention. You may have different signs and symptoms depending on the type and severity of the heart inflammation that you have.

The treatment your doctor recommends may depend on whether you are diagnosed with inflammation of the lining of your heart or valves, the heart muscle, or the tissue surrounding the heart. You may be treated with medicine, procedures, or possibly surgery to treat your condition and its complications. Complications may include an arrhythmia, or irregular heartbeat, and heart failure. As a precaution, EC19V recommends that vaccinated persons, in particular adolescents and younger men, should avoid strenuous physical activity for one week after their second dose.

During this time, they should seek medical attention promptly if they develop chest pain, shortness of breath or abnormal heartbeats. In every patient with pericarditis, restriction of physical activity is recommended until symptoms have resolved and inflammatory markers have normalized. If a systemic disease is identified as the cause of pericarditis, therapy should be focused on treating the underlying condition. For instance, antibiotics will be required for a patient with tuberculosis, and chemotherapy or other treatments will be required in a patient with neoplastic pericarditis. Another important consideration is whether the affected individual needs to be admitted to the hospital or can be treated as an outpatient. Although most patients can be treated outside the hospital, patients with high-risk features are usually admitted.

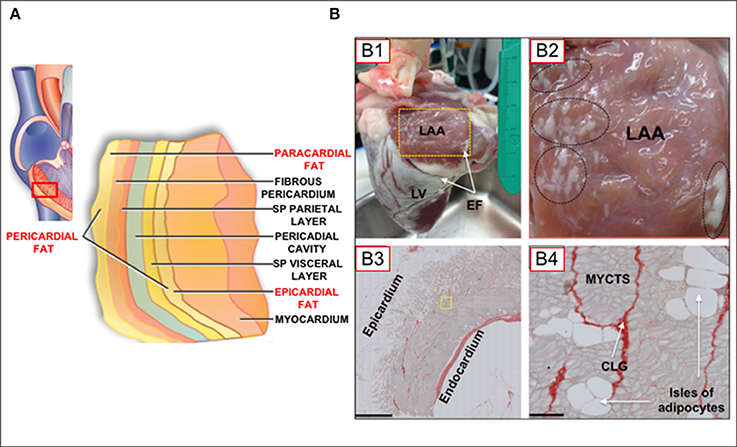

These features include fever, a slow onset of disease without sudden onset of chest pain, presence of a large pericardial effusion, use of immunosuppressant medications or blood thinners or high troponin levels . Clinicians should be aware of the risk of myocarditis and pericarditis with mRNA vaccines and those most likely to be affected. They should be alert to presentations such as acute chest pain, shortness of breath and palpitations that may be suggestive of myocarditis after vaccination, especially in adolescent or young males. Coronary events are less likely to be the source of such symptoms among younger people. The pericardium is a double-walled sac in which the heart and the roots of the great vessels are contained . The pericardial sac encloses the pericardial cavity which contains pericardial fluid.

Numerous conditions may cause inflammation in the pericardium, the pericardial cavity and/or the myocardium. Pericarditis refers to inflammation of the pericardium, and myocarditis refers to inflammation of the myocardial tissue. However, it is often difficult to differentiate pericarditis and myocarditis, and they tend to accompany each other. Therefore, the term perimyocarditisis often used in clinical practice . The etiology, clinical characteristics and ECG features of pericarditis will be discussed here. From a clinical point of view, clinicians must be able to separate pericarditis from ST elevation myocardial infarction .

This may not always be simple, because both conditions bring about severe chest pain and ST elevations on the ECG. However, as we will discuss below, it is actually rather straightforward to distinguish these two conditions. Myocarditis and pericarditis are uncommon conditions, usually thought to be related to viral infection leading to inflammation of the heart muscle or the tissue surrounding the heart. Diagnosis is based on elevated levels of cardiac enzymes and specific cardiac tests of electrical activity and structure . Rates of incidence vary between populations and by gender and age; for example, the incidence in adolescent males aged 14 to 18 years is consistently higher than in females.

Estimates of how common these occur depend on how carefully the diagnosis is being looked for.Those recovering from myocarditis are advised to avoid strenuous exercise until fully recovered. Severity of myocarditis and pericarditis cases can vary, but "reports have increased since April, mostly in young males 16 and older, several days after vaccination, and more often after the second vaccine dose. Dr. Fryhofer also is a member of ACIP's COVID-19 Vaccine Work Group. The cause of pericarditis often remains unknown but is believed to be most often due to a viral infection.

Other causes include bacterial infections such as tuberculosis, uremic pericarditis, heart attack, cancer, autoimmune disorders, and chest trauma. Diagnosis is based on the presence of chest pain, a pericardial rub, specific electrocardiogram changes, and fluid around the heart. Usually acute pericarditis causes fever and sharp chest pain, which often extends to the left shoulder and sometimes down the left arm.

The pain may be similar to that of a heart attack, except that it tends to be made worse by lying down, swallowing food, coughing, or even deep breathing. The accumulating fluid or blood in the pericardial space puts pressure on the heart, interfering with its ability to pump blood. If the pressure is too high, cardiac tamponade—a potentially fatal condition—may occur. Acute pericarditis can have a similar presentation to myocarditis, with chest pain and shortness of breath, and patients can also have concurrent myocardial involvement, known as myopericarditis. Treatment of pericarditis is aimed at the cause, with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs the mainstay of therapy for viral, idiopathic and pericarditis associated with a systemic inflammatory disease. The long-term prognosis of pericarditis is good, but it can become recurrent and rarely patients can develop constrictive pericarditis.

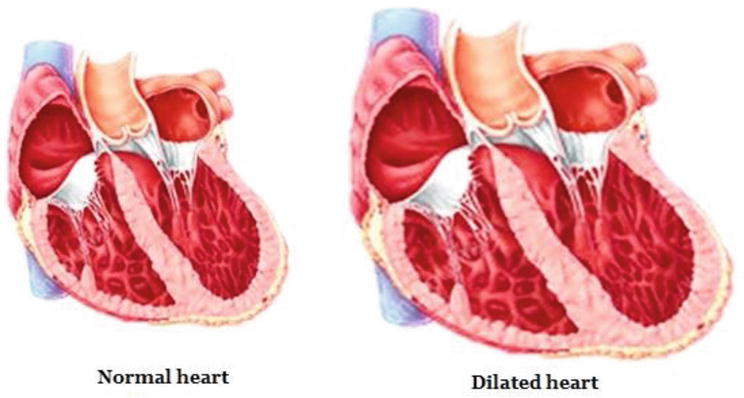

Presentation of acute myocarditis is variable, ranging from subclinical disease to heart failure and patients can present with chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations and fatigue. Most patients respond well to standard treatment, and the prognosis is good. However, it can progress to dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic heart failure, with evidence implicating it in 12% of sudden deaths in adults aged under 40. Whenever you feel chest pains, make sure to visit a doctor immediately or dial for emergency assistance.

While many cases of pericarditis can go away without medical treatment, it can sometimes develop into a more serious condition called cardiac tamponade. This occurs when fluid collects in the pericardium, preventing the heart from filling properly and causing a drop in blood pressure that can be fatal. Receiving an early diagnosis can help prevent these complications and help ensure that you aren't experiencing a more serious heart condition. Symptoms of pericardial problems include chest pain, rapid heartbeat, and difficulty breathing. Your doctor may use a physical exam, imaging tests, and heart tests to make a diagnosis.

Healthcare providers should consider myocarditis and pericarditis in evaluation of acute chest pain or pressure, arrhythmias, shortness of breath or other clinically compatible symptoms after vaccination. They should consider doing an electrocardiogram , troponins, and an echocardiogram, in consultation with a cardiologist. An essential part of the physical examination is auscultation of the heart using a stethoscope; in some patients, a characteristic scratching sound, known as a pericardial friction rub, may be heard. The physical exam can also show signs of cardiac tamponade or constrictive pericarditis, such as dyspnea, distended neck veins, edema, or low blood pressure.

Myocarditis is inflammation of the muscle of the heart, and pericarditis is inflammation of the tissue that forms a sac around the heart. It can also be caused by autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, certain medications, heavy metals, and radiation treatments. The symptoms are chest pain, shortness of breath, or an abnormal heartbeat . Symptoms can include chest pain, pressure or discomfort, shortness of breath, and palpitations. Traditional myocarditis can be treated with supportive care, such as oxygen or fluids, anti-inflammatory medicines, or in severe cases, with mechanical support or a heart transplant. Unlike the incidents related to the vaccines, traditional myocarditis is usually more severe.

But for both cases, patients must reduce exercise for three to six months. Patients with viral or idiopathic pericarditis are treated with a combination of colchicine and either aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen, naproxen or indomethacin. This medication combination is also the first line of treatment in most patients with recurrent pericarditis. These medications are continued at least until symptoms have resolved and inflammatory markers have normalized. In patients with contraindications to NSAIDs or no improvement with first-line therapy, NSAIDs can be replaced with prednisone, a corticosteroid drug with powerful anti-inflammatory properties.

Patients who still have symptoms despite treatment with colchicine and prednisone may benefit from addition or continuation of a NSAID. In refractory cases, other therapies may be used, although their efficacy has yet to be confirmed in controlled clinical trials. These therapies inhibit the immune system to decrease inflammation and include azathioprine, methotrexate and intravenous immune globulins . For those not admitted to hospital, follow-up should be within a week of presentation if symptoms are improving.

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of pericarditis should refrain from high intensity or competitive sports for 3-4 weeks or until resolution of symptoms and normalization of laboratory markers, ECG and imaging. Further, patients with a confirmed diagnosis of myocarditis and some cases of pericarditis may require exercise modification for at least 1 month or as recommended by their specialist . While symptoms and signs of myocarditis and pericarditis resolve within a few days with supportive care, long-term effects are unknown and outcomes are expected to be good. Your risk of pericarditis is higher after a heart attack, heart surgery , radiation therapy or a percutaneous treatment, such as cardiac catheterization or radiofrequency ablation .

In these cases, it is likely that the inflammation of the pericardium is an error in the body's response to the procedure or condition. It can sometimes take several weeks for symptoms of pericarditis to develop after bypass surgery. If your symptoms last fewer than three weeks, you will be diagnosed with acute pericarditis.