The ideal gas equation and the ideal gas constant, which express the ideal gas law provide a means for calculating air density for different pressures and temperatures. Although this article is primarily about determining the density of air, the density of other gases at known temperature and gas pressure can also be estimated using the ideal gas law in the same way. On this slide you will find typical values of the properties of air at sea level static conditions for a standard day. We are all aware that pressure and temperature of the air depend on your location on the earth and the season of the year. And while it is hotter in some seasons than others, pressure and temperature change day to day, hour to hour, sometimes even minute to minute during severe weather. The values presented on the slide are simply average values used by engineers to design machines.

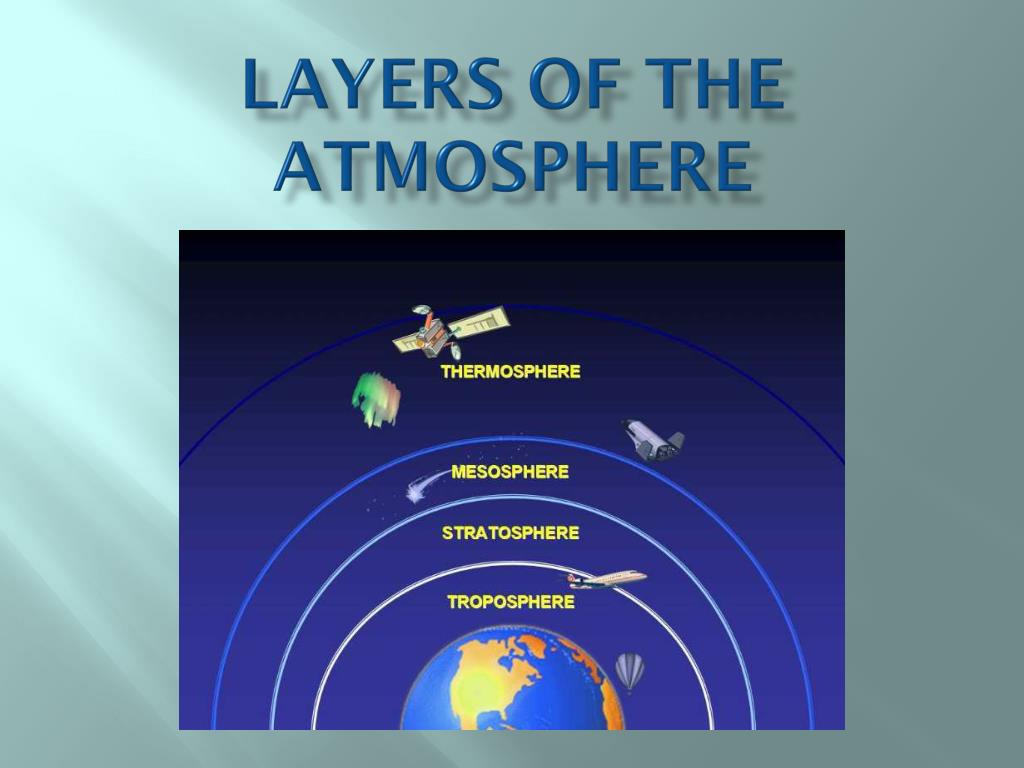

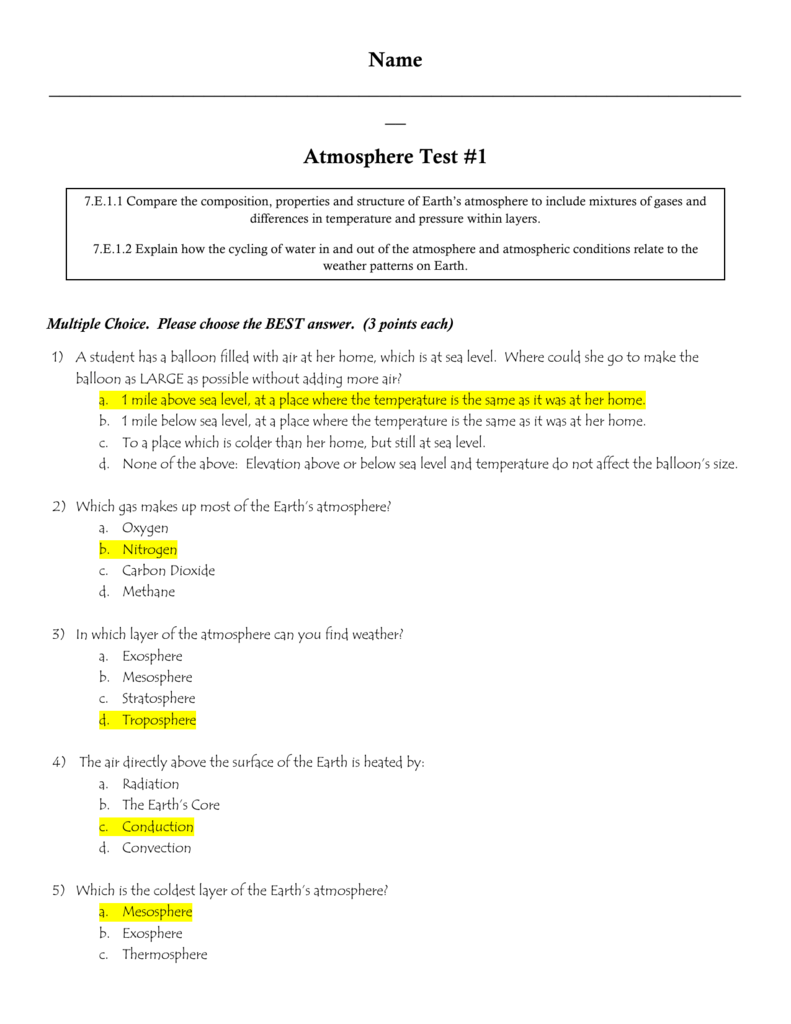

We also know that all of the state-of-the-gas variables will change with altitude, which is why the typical values are given at sea level, static conditions. Because the gravity of the Earth holds theatmosphere to the surface, as altitude increases, air density, pressure, and temperature decrease. The variation of the air from the standard can be very important since it affects flow parameters like the speed of sound. For a better understanding of how temperature and pressure influence air density, let's focus on a case of dry air.

It contains mostly molecules of nitrogen and oxygen that are moving around at incredible speeds. Use our particles velocity calculator to see how fast they can move! For example, the average speed of a nitrogen molecule with a mass of 14 u (u - unified atomic mass unit) at room temperature is about 670 m/s - two times faster than the speed of sound! Moreover, at higher temperatures, gas molecules further accelerate.

As a result, they push harder against their surroundings, expanding the volume of the gas . And the higher the volume with the same amount of particles, the lower the density. Therefore, air's density decreases as the air is heated. This term is roughly the total translational kinetic energy of N molecules at an absolute temperature T, as we will see formally in the next section. The left-hand side of the ideal gas law equation is pV.

As mentioned in the example on the number of molecules in an ideal gas, pressure multiplied by volume has units of energy. The energy of a gas can be changed when the gas does work as it increases in volume, something we explored in the preceding chapter, and the amount of work is related to the pressure. This is the process that occurs in gasoline or steam engines and turbines, as we'll see in the next chapter. The behavior of gases can be described by several laws based on experimental observations of their properties. The pressure of a given amount of gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature, provided that the volume does not change (Amontons's law).

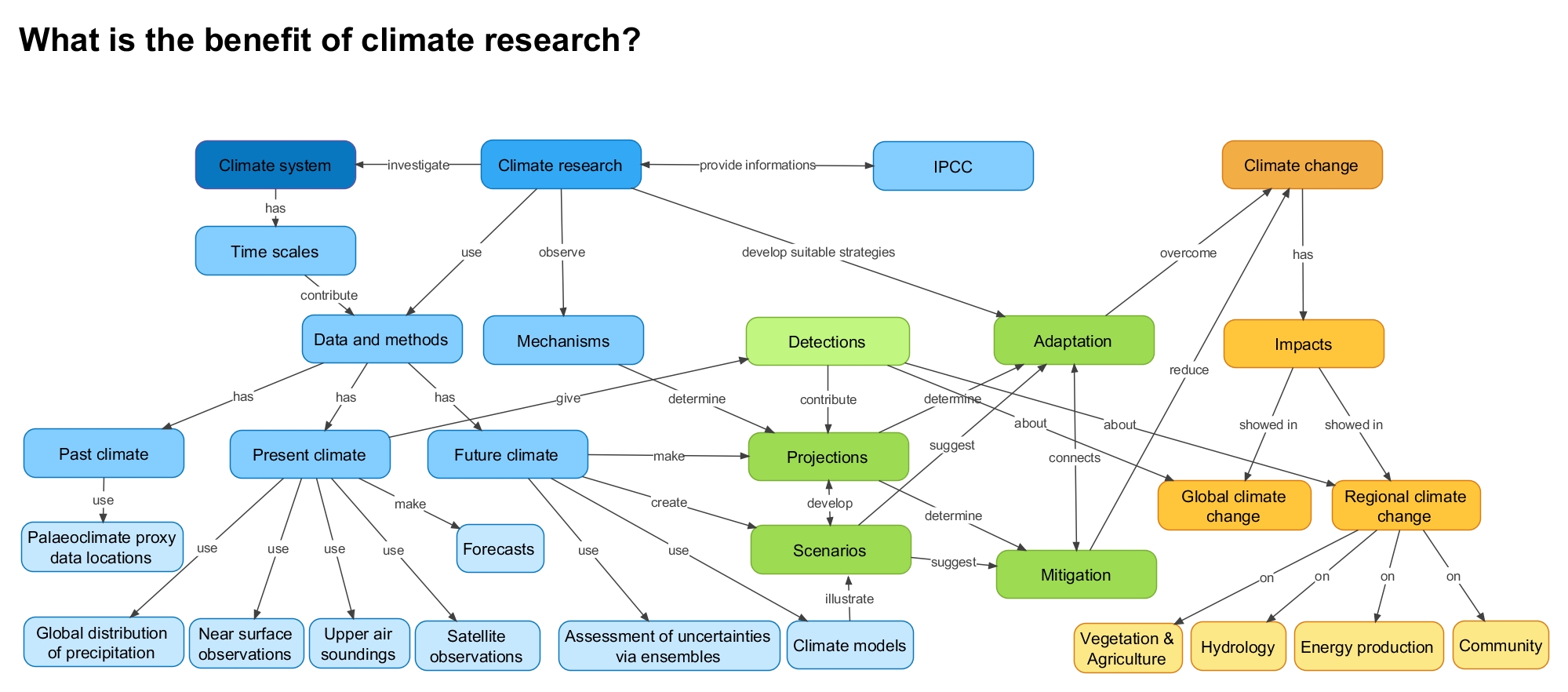

The volume of a given gas sample is directly proportional to its absolute temperature at constant pressure (Charles's law). The volume of a given amount of gas is inversely proportional to its pressure when temperature is held constant (Boyle's law). Under the same conditions of temperature and pressure, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of molecules (Avogadro's law). An online air density calculator such as the one by Engineering Toolbox let you calculate theoretical values for air density at given temperatures and pressures. The website also provides an air density table of values at different temperatures and pressures. These graphs show how density and specific weight decrease at higher values of temperature and pressure.

Air density equations Air contains a mixture of dry air and water vapor. The amount of water vapor is a function of the relative humidity; it is also related to the dew point temperature of the air. The density of air is usually denoted by the Greek letter ρ, and it measures the mass of air per unit volume (e.g. g / m3). Dry air mostly consists of nitrogen (~78 %) and oxygen (~21 %). The remaining 1 % contains many different gases, among others, argon, carbon dioxide, neon or helium.

However, the air will cease to be dry air when water vapor appears. Eventually, these individual laws were combined into a single equation—the ideal gas law—that relates gas quantities for gases and is quite accurate for low pressures and moderate temperatures. We will consider the key developments in individual relationships , then put them together in the ideal gas law. Note that every molecule listed is heavier that or equal to 18 u. Now, let's add some water vapor molecules to the gas with the total atomic weight of 18 u (H₂O - two atoms of hydrogen 1 u and one oxygen 16 u). According to Avogadro's law, the total number of molecules remains the same in the container under the same conditions .

It means that water vapor molecules have to replace nitrogen, oxygen or argon. Because molecules of H₂O are lighter than the other gases, the total mass of the gas decreases, decreasing the density of the air too. This is a good question to ask, because the air in a pipe friction loss, drag force, or pitot tube calculation, is indeed a real gas, not an ideal gas. Fortunately, however, many real gases behave almost exactly like an ideal gas over a wide range of temperatures and pressures. The ideal gas law doesn't work well for very low temperatures or very high gas pressures . For many practical, real situations, however, the ideal gas law gives quite accurate values for the density of air at different pressures and temperatures.

This phenomenon is wonderful for those who enjoy helium-filled balloons at parties or like to give them to send greetings, or for those who use them for advertising. Scientists who perform atmospheric research use helium-filled weather balloons to carry various measuring instruments into the atmosphere. You are probably familiar with the Goodyear blimp, which uses helium to stay afloat.

The Goodyear blimp website contains technical information about the blimps, including their volumes and maximum gross weights. If you use the ideal gas law, the molecular weights shown above and the appropriate unit conversions, you should calculate gross weights close to those stated on the web site. The density of air depends on many factors and can vary in different places. It mainly changes with temperature, relative humidity, pressure and hence with altitude . The air pressure can be related to the weight of the air over a given location. It is easy to imagine that the higher you stand, the less air is above you and the pressure is lower (check out our definition of pressure!).

Therefore, air pressure decreases with increasing altitude. In the following text, you will find out what is the air density at sea level and the standard air density. For any ideal gas, at a given temperature and pressure, the number of molecules is constant for a particular volume (see Avogadro's Law). So when water molecules are added to a given volume of air, the dry air molecules must decrease by the same number, to keep the pressure or temperature from increasing.

The calculator below can be used to calculate the air density and specific weight at given temperatures and atmospheric pressure. Gases whose properties of P, V, and T are accurately described by the ideal gas law are said to exhibit ideal behavior or to approximate the traits of an ideal gas. An ideal gas is a hypothetical construct that may be used along with kinetic molecular theory to effectively explain the gas laws as will be described in a later module of this chapter. Although all the calculations presented in this module assume ideal behavior, this assumption is only reasonable for gases under conditions of relatively low pressure and high temperature. In the final module of this chapter, a modified gas law will be introduced that accounts for the non-ideal behavior observed for many gases at relatively high pressures and low temperatures.

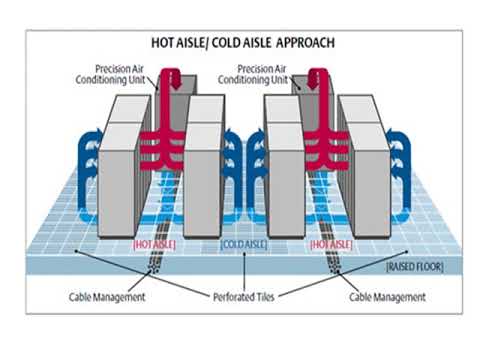

One form of numerical simulation of flow and particle capture by air filter media sees gases as continuous fluids, influenced by the macro-properties viscosity, density, and pressure. The alternate approach treats gases as atoms or molecules in random motion, impacting their own kind and solid surfaces on a micro-scale. The appropriate form for analysis of flow through a given filter medium at a given operating condition depends on the gas condition and the Knudsen number of the finest fibers in the filter medium simulated. Continuum, macro-scale methods may be usable for media with individual fiber Kn as high as 0.01.

Part I of this article discussed simulations of air filter media performance, where all fibers are in the continuum flow regime and the Navier-Stokes equation with a finite-volume solution is applicable. Here, Part II discusses filter media performance simulation by computational approaches other than numerical solutions of the Navier-Stokes equation. These include use of the Burnett, super-Burnett, and Grad moment equations; lattice Boltzmann and direct simulation Monte Carlo methods; and the molecular dynamics, boundary singularity, and boundary element methods. Relates the pressure, volume, temperature and number of moles in a gas to each other. The ideal gas law is what is called an equation of state because it is a complete description of the gas's thermodynamic state. No other information is needed to calculate any other thermodynamic variable, and, since the equation relates four variables, a knowledge of any three of them is sufficient.

Under ordinary conditions, such as those of the air around us, the difference is that the molecules of gases are much farther apart than those of solids and liquids. Also, at temperatures well above the boiling temperature, the motion of molecules is fast, and the gases expand rapidly to occupy all of the accessible volume. In contrast, in liquids and solids, molecules are closer together, and the behavior of molecules in liquids and solids is highly constrained by the molecules' interactions with one another. The macroscopic properties of such substances depend strongly on the forces between the molecules, and since many molecules are interacting, the resulting "many-body problems" can be extremely complicated .

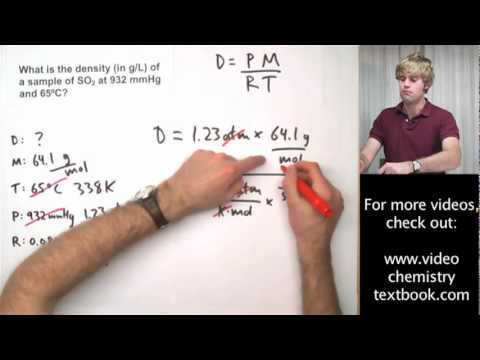

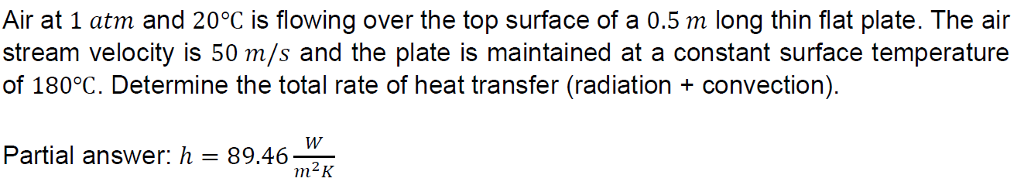

In which ρ is density in units of m/V mass/volume (kg/m3). Keep in mind this version of the ideal gas law uses the R gas constant in units of mass, not moles. The ideal gas law can be considered to be another manifestation of the law of conservation of energy . Work done on a gas results in an increase in its energy, increasing pressure and/or temperature, or decreasing volume. This increased energy can also be viewed as increased internal kinetic energy, given the gas's atoms and molecules.

At room temperatures, collisions between atoms and molecules can be ignored. In this case, the gas is called an ideal gas, in which case the relationship between the pressure, volume, and temperature is given by the equation of state called the ideal gas law. Oxygen - Density and Specific Weight vs. Temperature and Pressure - Online calculator, figures and tables showing density and specific weight of oxygen, O2, at varying temperature and pressure - Imperial and SI Units. Helium - Density and Specific Weight vs. Temperature and Pressure - Online calculator, figures and tables showing density and specific weight of helium, He, at varying temperature and pressure - Imperial and SI Units. If we can treat air as an ideal gas, then the ideal gas law in this form can be used to calculate the density of air at different pressures and temperatures. Where the constant of proportionality, , is called the dynamic viscosity.

Equation 7-8 is known as Newton's law of viscosity, and fluids that conform to this law are referred to as Newtonian fluids. Common liquids such as water, oil, glycerin, and gasoline are Newtonian fluids as are common gases such as air, nitrogen, hydrogen and argon. The value of the dynamic viscosity depends on the fluid. Liquids have higher viscosities than gases, and some liquids are more viscous than others. For example, oil, glycerin and other gooey liquids have higher viscosities than water, gasoline, and alcohol.

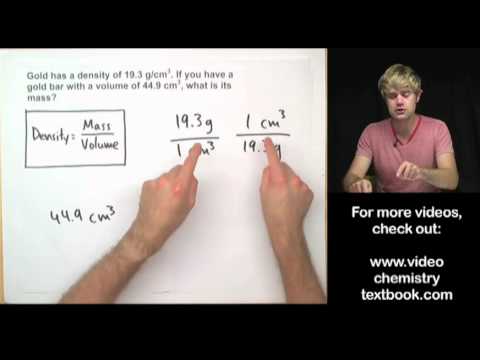

The viscosities of gases do not vary significantly from one gas to another, however. A common use of Equation 6.3.9 is to determine the molar mass of an unknown gas by measuring its density at a known temperature and pressure. This method is particularly useful in identifying a gas that has been produced in a reaction, and it is not difficult to carry out.

A flask or glass bulb of known volume is carefully dried, evacuated, sealed, and weighed empty. It is then filled with a sample of a gas at a known temperature and pressure and re-weighed. The difference in mass between the two readings is the mass of the gas. The volume of the flask is usually determined by weighing the flask when empty and when filled with a liquid of known density such as water. The use of density measurements to calculate molar masses is illustrated in Example 10.

To get a better idea of the density of air specifically, you need to account for how air is made of different gases when formulating its density. At a constant temperature, pressure and volume, dry air is typically made of 78% nitrogen (N2), 21% oxygen (O2) and one percent argon (Ar). Air pressure is a physical property of a gas that tells us with how much strength it has when acting on the surroundings. Let's consider a cubic container with some air closed inside.

According to the kinetic theory of gases, the molecules of the gas are in constant motion with a velocity that depends on the thermal energy. Particles collide with each other and with the walls of a container, exerting a tiny force on them. However, since the number of the enclosed molecules reaches about ~10²³ (order of magnitude of Avogadro's constant), the total force becomes significant and measurable - this is pressure.

Argon - Density and Specific Weight - Online calculator, figures and tables showing density and specific weight of argon, Ar, at varying temperature and pressure - Imperial and SI Units. Air - Specific Heat vs. Temperature at Constant Pressure - Online calculator with figures and tables showing specific heat of dry air vs. temperature and pressure. In a closed container partly filled with water there will be some water vapor in the space above the water. The concentration of water vapor depends only on the temperature. It is not dependent on the amount of water and is only very slightly influenced by the pressure of air in the container. The water vapor exerts a pressure on the walls of the container.

The empirical equations given below give a good approximation to the saturation water vapor pressure at temperatures within the limits of the earth's climate. A property is a physical characteristic or attribute of a substance. Matter in either state, solid or fluid, may be characterized in terms of properties. For example, Young's modulus is a property of solids that relates stress to strain. Density is a property of solids and fluids that provides a measure of mass contained in a unit volume.

Density Of Air At 20C In this section, we examine some of the more commonly used fluid properties. Specifically, we will discuss 1) density, specific weight, and specific gravity, 2) bulk modulus, and 3) viscosity. When administered in relatively high concentrations the mechanical properties of inhaled gas can become significantly different from air.

This fact has implications in mechanical ventilation where adequate respiration and injury to the lungs or respiratory muscles can worsen morbidity and mortality. Here we use an engineering pressure loss model to analyze the administration of medical gas mixtures in newborns. The model is used to determine the pressure distribution along the gas flow path. Numerical experiments comparing medical gas mixtures with helium, nitrous oxide, argon, xenon, and medical air as a control, with and without an endotracheal tube obstruction were performed. The engineering pressure loss model was incorporated into a model of mechanical ventilation during pressure control mode, a ventilator mode that is often used for neonates. Results are presented in the form of Rohrer equations relating pressure loss to flow rate for each gas mixture with and without obstruction.

These equations were incorporated into a model for mechanical ventilation resulting in pressure, flow rate, and volume curves for the inhalation-exhalation cycle. In terms of accuracy, published values of airway resistance range from 50 to 150 cmH2O/L per second for a normal 3 kg infant. With air, the current results are 55 to 80 cmH2O/L per second for 0.3 to 5 L/min. It is shown that density through inertial pressure losses has a greater influence on airway resistance than viscosity in spite of relatively low flow rates and small airway dimensions of newborns. The results indicate that the high-density xenon mixture can be problematic during mechanical ventilation. On the other hand, low density heliox provides a wider margin of safety for mechanical ventilation than the other gas mixtures.

The argon or nitrous oxide mixtures considered are only slightly different from air in terms of mechanical ventilation performance. At constant pressure, the volume of a gas is proportional to the absolute temperature. (Law of Gay-Lussac) The pressures on the inside and outside of the inflated balloon are nearly equal.

The pressure on the outside is the constant atmospheric pressure. The pressure in the freezer is atmospheric pressure, the temperature in the freezer is lower that the outside temperature, so the volume of the balloon decreases when it is placed into the freezer. The ideal gas law allows us to calculate the value of the fourth variable for a gaseous sample if we know the values of any three of the four variables . It also allows us to predict the final state of a sample of a gas (i.e., its final temperature, pressure, volume, and amount) following any changes in conditions if the parameters are specified for an initial state.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.